Creating an unsolicited master plan of New York City, designing a utopia in New Jersey: just two of the projects self-initiated by Adam Frampton’s Only If architecture studio. On a smaller scale, the Manhattan-based outfit recently completed a fashion showroom featuring mirrored, movable modules and a coffee bar that eschews the bulb-lit, white-tiled laboratories of recent years in favour of efficiency, black marble and budget-friendly painted OSB.

Frampton earned degrees in architecture and environmental design (with honours) at Princeton University and the University of Colorado Boulder before working in Rotterdam and Hong Kong for OMA; leading projects in China, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and India; and coauthoring a book on Hong Kong urbanism. Registered to practise in both the Netherlands and the US, Frampton opened Only If in 2013. The studio ‘embraces organization over appearance, experimentation over repetition, simplicity over complexity, and materialization over theorization’. This year Frampton and his team are designing two buildings from the ground up, but he’s quick to point out that there’s always something to be learned from interiors as well.

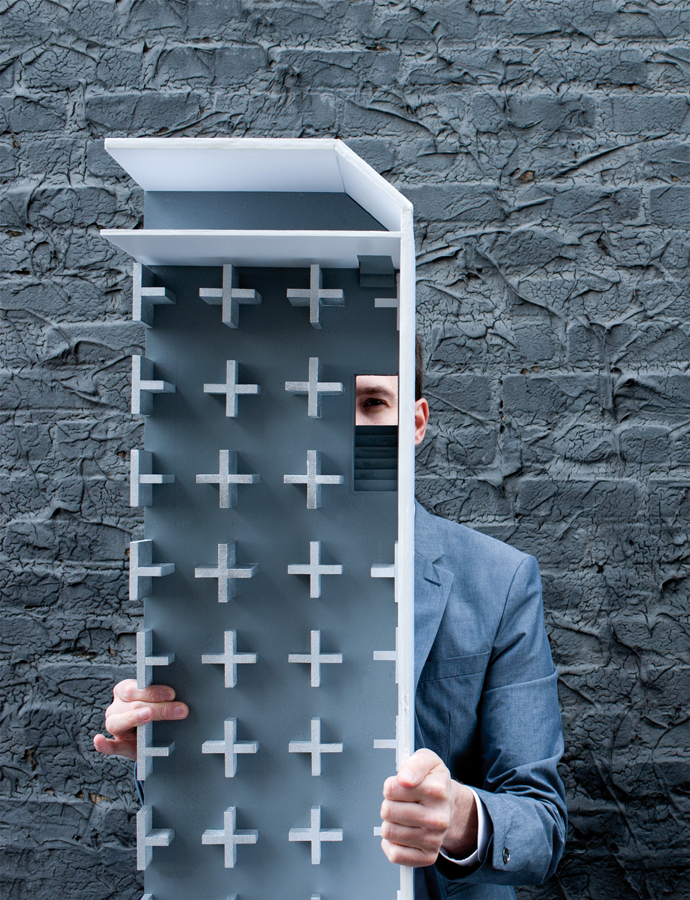

Portrait Cindy Baar

Why settle in New York and not in one of the booming Asian cities you’ve worked in?

ADAM FRAMPTON: A constant refrain is that New York is too expensive and that the conditions that made it so creative in the past are being eroded. This is completely true, but I still find New York unbelievably vital and cosmopolitan in a way that supports creative practice. The talent of architects and designers that have collaborated with Only If – most of whom are not from here – is possible only because of our location, as is the density of ambitious clients and an environment of discussion. All of this outweighs the very real burden of our overhead.

As an architect, what is interesting to you about doing interiors?

Interiors provide an immediate and direct testing ground for ideas. Because of the time and resources required in larger architectural projects, there’s more delay between design and realization. So interiors offer speed, and perhaps more control. The different skills required in interior design expand our own capabilities, and working in more intuitive ways is refreshing. Eventually we’d like to work on many different scales at the same time.

Does anything from large-scale architecture translate into small-scale interiors, or vice versa?

Each of the different scales at which we work – interior, architectural and urban – requires its own expertise and therefore might be considered autonomous. In spite of the separation between scales, however, there is always the possibility of communication. Architectural thinking produces rigour in the design of interiors. Reciprocally, the material sensibility we’ve cultivated through smaller projects is already translating to other scales. We did a larger building that required us to consider the resolution between two parts, which we conceived like a reveal – something typically found between a floor and a wall where you need some tolerance or looseness. Perhaps this is more like a form of creative mistranslation: some things are lost in the process of translation, but new meanings can be gained.

Photos Michael Vahrenwald (Esto)

Is it interesting to do an interior within the constraints of architecture designed by someone else?

Every project has its own set of constraints. We deliberately selected a highly constrained site for a narrow house we’re designing now in Brooklyn. This forces interesting solutions that might not have occurred otherwise. But I’ve also worked in more tabula-rasa situations. While freedom may be easier, it can make it more difficult to achieve a kind of specificity that often enriches a design.

How have you seen architecture changing as consumer values and technologies change, and how does your practice fit into this transformation?

There is an increasing degree of complexity in any given project, even smaller ones. This is especially true in the US. Architecture seems to be in a sort of late baroque period now, with parametric design and digitally driven methods allowing designers to impose or produce additional formal complexity on top of already complex systems. Without rejecting the possibilities of new tools or technologies, our practice resists this approach. We look for simple gestures and forms that produce structure, coherence and identity. The use of physical models reinforces our way of working. Even Voyager Espresso, which has an unexpectedly figural plan for such a small space, consists of relatively straightforward circular and linear geometries. Simplification of form perhaps also liberates us to focus on broader questions about the city, collectivity and their relationship with the environment.

There are no coffeehouse clichés in Voyager. How do you avoid clichés, and do they ever have value?

Fortunately, most of our clients are more interested in the experimental than the formulaic. But what constitutes these territories isn’t always apparent – even for the designer, who might not be conscious of the banal repetition of a certain idea, or may even be responsible for it. Our process, therefore, is to start by trying to identify the existing clichés and tropes – in other words, to define a negative position from which we can start. This usually takes the form of a visual inventory and is recorded in booklets that we produce in the office, which can be referred to during the next steps of a project. This process allows us to create images and designs that hopefully define a new position.

Also, I would distinguish cliché from the generic or everyday, which I do think has some value. Consider, for instance, the beauty of repetition and the subtle variation of structures in Hilla and Bernd Becher’s photographs. Working through known forms and materials is also something we try to do. Not every aspect of a project needs to be novel or different.

only-if.org

Read more interesting interviews from designers around the world in Frame #111. Get your copy in the Frame Store.

-Cropped-thumb.jpg)

-thumb.jpg)

-thumb.jpg)

-thumb.jpg)